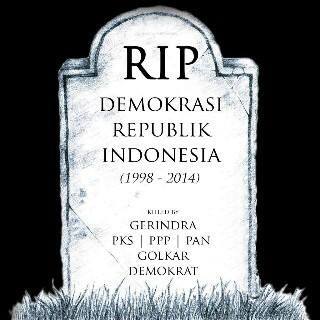

Tombstone by Yuda Pratama (and SBY)

So it has happened: Indonesia’s democracy has been undermined by the nation’s elected representatives. When I wrote a fortnight ago about the threat posed by parliament’s discussion of the local election bill, I was still hopeful. In a month of travel in Eastern Indonesia, everyone I met — coffee farmers, school teachers, ojek drivers, clan heads — spoke volubly and with next to no prompting about their RIGHT to choose their district head (bupati) or mayor. These are the people who have most to lose if the choice of district head is taken away from them and handed over to a small coterie of political party hacks in the local legislatures. Most of these voters have become so used to the idea that they can, at least once in five years, go to the polls and decide who governs them that they simply can’t believe the right to elect their leaders directly might be abrogated.

Urban Indonesians exposed to more media obviously felt otherwise. They are deeply cynical about the 560 members of the national parliament; many believe that MPs serve the interest of their political parties first and foremost. The MPs’ own back account comes a close second. It is only after those things are taken care of that they spare a thought for the constituents in far-flung places that they barely visit except during campaign season. Indonesia’s city kids organised though Facebook, Twitter and other networks to stage demonstrations against the proposed bill in a dozen major cities.

To no avail. The discussions in the national parliament last Thursday went on well past midnight. By Friday morning, we learned that the bill to undermine local democracy in Indonesia had passed in the most dramatic way. Legislators from the ruling Democrat Party walked out of the vote, withdrawing 124 votes that would have killed the bill and preserved democracy. They did this while Indonesia’s current President Susilo Bambang Yudhuyono, who happens also to head the Democrats, was out of the country. Since he had in the past supported direct elections for district head, this allowed him to express disappointment at an outcome that his party could so easily have reversed.

There’s a lot of speculation about if and why SBY allowed the walkout; whatever the truth of it, being associated with this democratic reverse is certainly is not going to improve his chances of getting the sort of high-profile international job he so craves when his term finishes late next month. It hasn’t done much for his image at home, either. #ShameOnYouSBY topped the Twitter board locally and internationally for over 24 hours.

Those political parties who support the shift to indirect elections say it will make politics more efficient and less expensive. They rarely mention that fact that we’ve been here before, that the first round of elections for district heads (mostly in 1999/2000) used the indirect system. The shift to direct elections was made because the indirect system was so thoroughly corrupt.

The real reason for the reversal is one the parties grouped in the coalition which lost the Presidential election are less likely to admit to: they are trying to resist what they perceive as a wave of civic empowerment which could sweep away the power of the Old Crocodiles who have for so long controlled party politics in Indonesia. The recent presidential elections have delivered victory to a man who came up through direct local elections and whose links with the established parties have been at best tenuous. Several of the more popular district leaders are also mavericks; some consider them a threat to the power of the national party structures.

Indirect local elections will allow parties to have a much greater say in who runs for office and therefore who wins as well as how they behave once they are in place. On the upside, it would allow party policies to be implemented more uniformly across the nation. This of course presupposes that parties actually have coherent policies — not something that was much in evidence during the last elections. On the downside, it will become virtually impossible to control collusion in local politics.

The new bill will certainly be challenged in the constitutional court, though since it simply reverts to an earlier system it’s not clear to me that there’s actually anything unconstitutional about it, only something undemocratic. I would expect that if the bill is upheld, Indonesians will take to the streets, and that the incoming administration will try to put the issue back on the legislative agenda rather rapidly. But since the incoming administration does not have anything like a majority in the new parliament, this may be an illustration of how precarious the next few years will be.

I draw hope from one thing: a small but not insignificant number of MPs from the Golkar and Democrat parties defied their leaders and sided with the parties that want to preserve people’s right to choose their leaders. Obviously, the Old Crocodiles still have the upper hand. But they must surely be aware that there are people within their own parties, as well as many millions more out on the streets of Indonesia, who are beginning to feel that they must be called to account.

A sad time for Indonesian political process, and even sadder that this happens on the eve of a new era as Jokowi (a “non crocodile”)is to be sworn in a president.

Kasar Betul. Learned those tricks from the West; then fine tuned it all.