In the USA, the quality of generic drugs is in the headlines again following a recent report by investigative journalists at ProPublica. They tested a total of 11 samples spread over three active ingredients, and found that two did not meet quality standards. In reporting their results, they gave figures for the amount of active quality surveillance conducted by the Mighty FDA. In a country with close to 350 million people, a country that spends over US$12,000 a year per person on healthcare, the drug regulator tested just over 50 medicine samples in their regular quality surveillance programme.

Reading this inspired me to bring together in a single post links to all of the studies that the STARmeds research programme on medicine quality in Indonesia has published. Just as a point of comparison, Indonesia is a country with close to 290 million people, that spends about US$ 130 a year per person on healthcare. The Indonesian drug regulator, BPOM, nonetheless manages to test over 15,000 medicine samples each year in regular quality surveillance.

Based at Universitas Pancasila in Jakarta, STARmeds collected and tested 1,274 samples of five common medicines. Pretending to be patients, our team walked into pharmacies around Indonesia and bought two antibiotics (amoxicillin and cefixime); one anti-hypertensive (amlodipine); a steroid (dexamethasone) and a gout medicine (allopurinol). We also sampled openly from hospitals and health centres, and bought samples off the internet. The (eye-wateringly) detailed methods are in the STARmeds study repository, and we have also posted the entire dataset, with details of every individual sample, its price, and its test results. We encourage others to answer all the questions our small team didn’t have time for.

Highlights, and the papers that describe the findings:

1) No relationship between price and quality

The cheapest medicines are just as likely to contain the correct amount of active ingredient and to dissolve in the time required by United States Pharmacopeia quality standards as the most expensive brands of the same product.

(A smaller study of different medicines in East Java found the same thing).

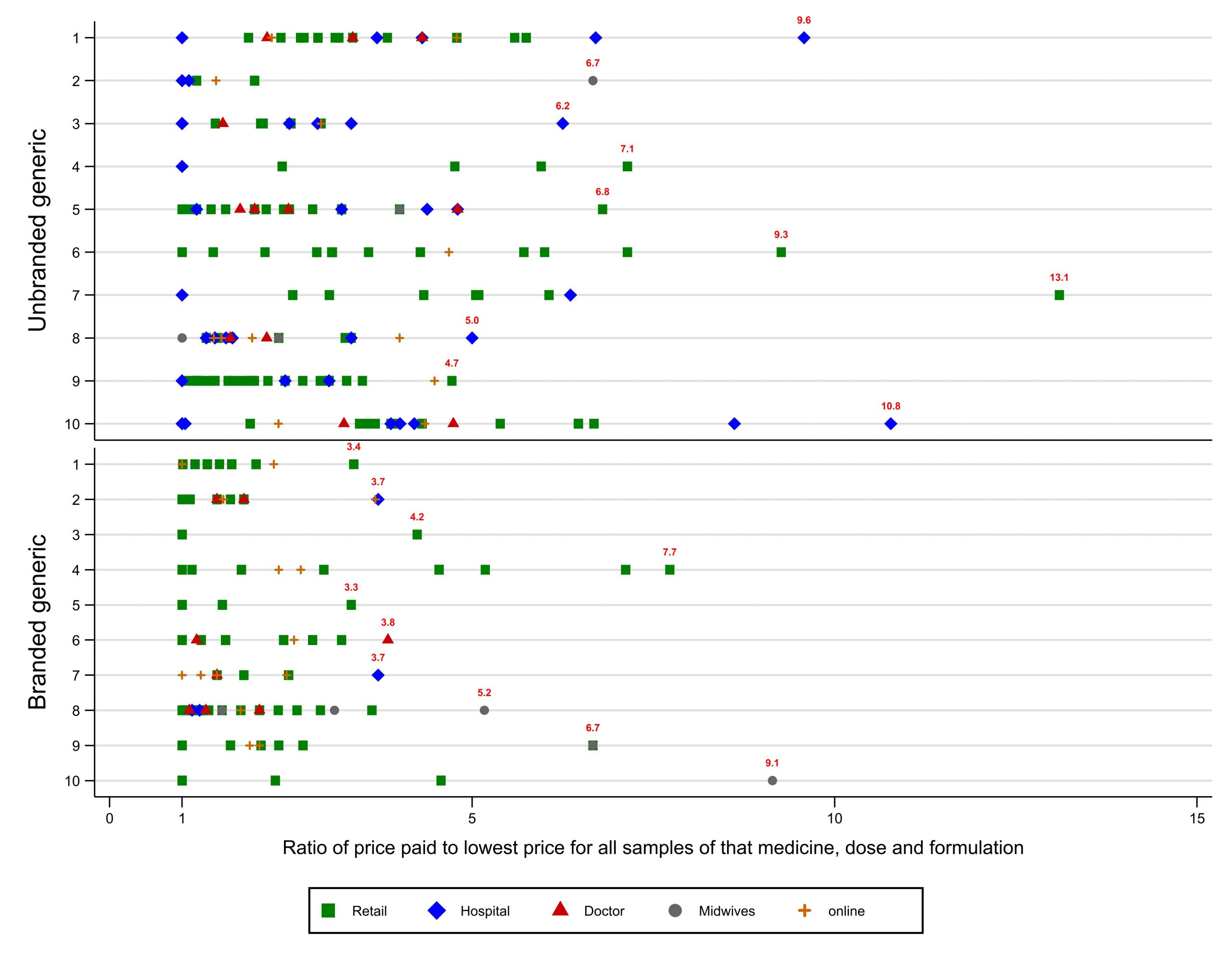

2) Insane price variation, but affordable options are available everywhere

For some medicines, the most expensive brand we found was priced at over 100 times the cheapest. Prices often varied three or four-fold for the very same brand, depending on the outlet. However, affordable options were available even in remote rural areas.

3) In estimating prevalence of poor quality medicines, market share is everything

Because they deliberately seek out a variety of brands, samples taken for studies are rarely representative. Weighting results by market size of different brands or manufacturers affects results dramatically; in our survey slashing prevalence estimates by 47%. In Indonesia, bad medicines don’t sell well.

4) Necessary adaptations of tests designed for rich pharma companies with well-equipped labs may lead to distorted results.

Because of a missing flask size, we made an error in early testing of amoxicillin; we suspect others have done the same, possibly affecting results of other published studies.

5) Price regulation isn’t very effective

Though Indonesia has elaborate rules to cap prices of unbranded generics and to introduce transparency for branded medicines, these are regularly ignored or flouted, especially by hospitals.

6) Surveillance based on random sampling from the market is expensive

The Mighty FDA is probably not wrong in claiming that close oversight of production is a more cost-effective way of protecting medicine quality. As medicine quality improves in a market, the value of random sampling falls.

7) Researchers should engage with policy audiences from the planning stages of their work

It’s hard work, but ultimately worthwhile,

STARmeds was funded by UK taxpayers under NIHR grant NIHR131145. Thank you.

Be the first to comment on "Indonesian medicine regulation: doing well compared with the Mighty FDA"