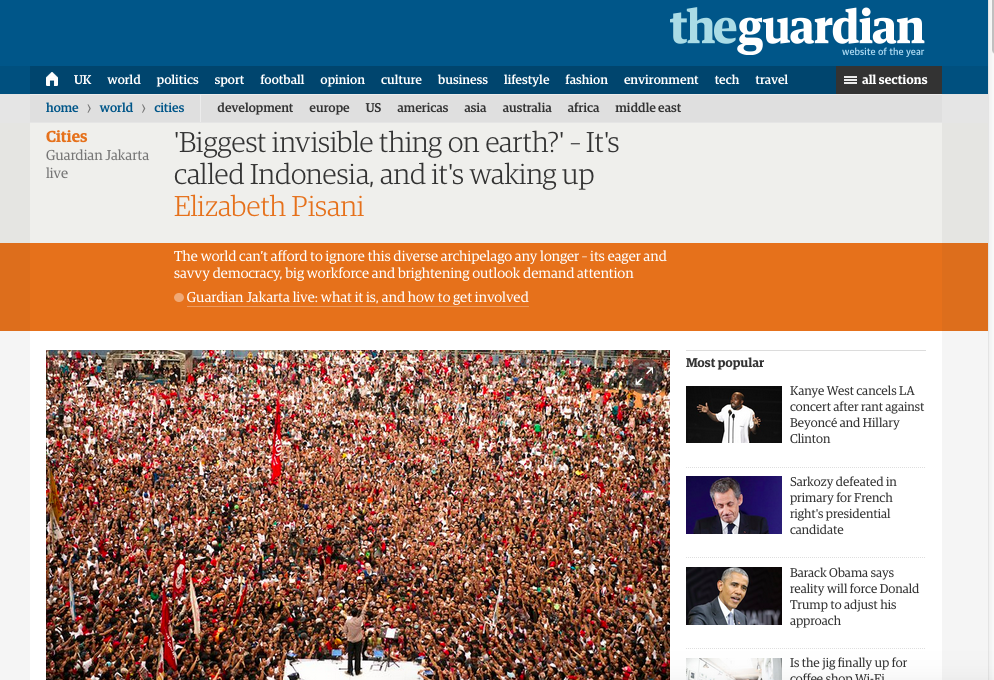

Earlier this month, tens of thousands of white-robed protesters stomped through the streets of Jakarta, baying for the blood of Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, aka Ahok. To simplify a complex story, Ahok stood accused of the sin of quoting the Quran while being Christian. In the best Indonesian tradition of rent-a-crowd politics, many of the “protesters” were there for the promise of money and a packed lunch; one told TV reporters that, though he came for the cash, he would of course continue to vote for Ahok because of what the no-nonsense governor had done to clean up the city’s corrupt bureaucracy.

No real surprises there, except perhaps to marvel at the pay for a day’s ranting-in-public. On the TV report, a shadow-faced protester said he was paid 200,000 rupiah (US$15), which is now 50% over Jakarta’s minimum wage. Ahok himself told ABC news others earned up to 500,000, or US$37 for the day. In several provinces in Indonesia, that’s just about the average monthly income. It’s certainly an interesting measure of inflation. If memory serves, during the last large political confrontation between supporters of Gus Dur and Megawati in 2001, protesters only earned 50,000 a day, around US$4 at the time, along with their nasi bungkus.

Some of my friends shrugged at these new demonstrations — just another expression of the well-established tradition of invoking the sacred to achieve profane political goals. But still, I always find the donning of religious uniforms to fight a political battle dispiriting. I was also cross with myself for leaving Jakarta for London the day before the demo; since it was barely covered in the European press, it made it that much harder to follow what was going on. Thank God for Twitter.

Right after the demo, when I was feeling somewhat sour about my Bad Boyfriend Indonesia, The Guardian asked if I’d write a piece to introduce their week-long series on Jakarta. They wanted me to explain “why Indonesia is such a point of global interest right now”. Hmmmmmmm. That’s a tough one; in the world which I inhabit — one of generally curious and internationally minded scientists, film-makers, restaurant owners, school teachers, bike shop owners — Indonesia is absolutely NOT a point of global interest. I said so. The Guardian editors agreed, and asked me to write about “why Indonesia SHOULD be a point of global interest, even though it isn’t”.

Update: Inflammatory headline alert: and it applies to both this blog post and to the article in the Guardian. The Guardian didn’t tell me what I could or couldn’t say. In fact, the editors actively encouraged me to tell it the way I saw it, and I did my best. But they then added a headline and sub-head which are not, in my view, supported by the facts as I interpret them.

As I said in the article, I am truly optimistic about the common sense of most Indonesian voters. I think decentralisation and democracy have created conditions in which that common sense can prevail in most places at most times. On Saturday, for example, Indonesians who support pluralism hit the streets (without being paid) to defend their country’s diversity. I spent last month in East Kalimantan and West, Central and North Sulawesi, and I found supporters of pluralism to be very much in the majority in city and village alike. But that does NOT necessarily mean that I agree that “The world can’t afford to ignore this diverse archipelago any longer” as the Guardian proclaimed. “Its eager and savvy democracy, big workforce and brightening outlook demand attention.” Hmmmmmmm again. I think Indonesia’s experience provides valuable lessons in “experimentalist democracy” (more about that in this very nerdy paper on health insurance, pdf). However, I think the world can and will continue to ignore Indonesia.

That’s not a pessimistic view. Or only mildly so. The world can afford to ignore Indonesia because even given the hopeful changes I outlined in the article, it will still punch below its weight economically. That’s partly because most of the “big workforce” in the the Guardian’s introductory sub-heading is not well equipped, either educationally or habitually, for highly productive work. But it’s also because of the nature of democracy itself. Successful democracy requires compromise, and compromise often leads to less-than-optimum distribution of resources. Call it pork-barrel politics (though not in Indonesia, where you may find yourself on trial for blasphemy if you do). Call it corruption (if you’re a Tea Party member with no desire to promote or preserve diversity). Or call it the cost of pluralism. The fact is, the more diverse a democracy, the more political compromise you need to glue it together. And Indonesia is probably the most diverse democracy in the world. A great deal of the country’s energy, attention and resources for many years to come will be turned inwards, focused on maintaining the exquisite balancing act that is Indonesian democracy.

On the plus side, the world can continue to ignore Indonesia because, despite the screeching of para-religious “mass organisations” and the machinations of their political puppeteers, the country’s leaders and most of its citizens understand the art of compromise. I believe that the nation will continue to manage the balancing act of democracy successfully. Thus, no major meltdown. Thus, no headlines in the global media, and no great demands on international attention. Sometimes, (other people’s) ignorance really is bliss.

(Updated on 22/11/16 to underline the mismatch between headline and content)