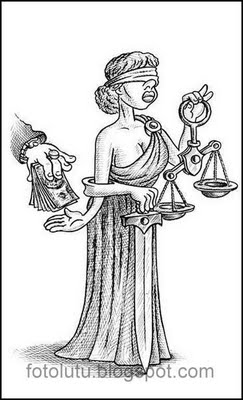

In pre-colonial times, the law in most areas of what is now Indonesia was doled out at the whim of the local ruler. Then along came the Dutch: they imposed several overlapping legal systems. Dutch law, with trained judges and prosecutors operating under a clear legal code, applied to Europeans (who from 1899 included the Japanese as well as “gazetted Europeans”: favoured “natives” whose names were published in the government gazette). Indigenous islanders were subject to local courts staffed by untrained clerks for criminal matters; for cases relating to the family, marriage, inheritance and much else they were judged either under religious law or according to local and ill-defined “adat” or traditional law. The religious law was of course mostly sharia law, which itself enshrines the idea that some people’s word (men’s, mostly) counts for more than other people’s. “Foreign Orientals” — Chinese and Arabs mostly — went to European courts for business-related cases, and local courts for everything else. In short, the concept of equality before the law simply did not exist.

Though Indonesians have governed themselves as an independent nation for 70 years, inequality in the face of the law seems still to be the norm. A couple of recent cases have underlined that in pretty upsetting ways. One: a woman has been jailed because in a private Facebook chat she told a friend that her husband was abusing her. Her husband, snooping around in her private correspondence (itself a pretty good indicator of abuse) found the comments and reported his wife to the police. Did the police investigate him for invasion of privacy? No. Did they try to find out whether the allegations were true and provide any kind of protection for the woman? No. They helped prepare a defamation case which has landed the woman in jail. While that tells us something general about how men’s word is valued over women’s it also tells us something about the absurdity of Indonesia’s legal system.

The other deeply dispiriting case of the last few weeks has been the 10 year jail sentence handed down to two school employees (Neil Bantleman, a Canadian, and Ferdinand Tjiong, an Indonesian) for allegedly sodomising three schoolboys with the help of a magic stone and some disappearing dungeons. The mother of one of the boys, who was also involved in an earlier case at the same school, is demanding US$125 million in damages. She seems vindicated in her belief that Indonesian judges would believe the children’s Harry Potter fantasy as long as the accused were the sort of push-button villains that Indonesian courts like to demonise. Right now, expatriates working in Indonesia seem to fall into that category. (For many other examples, mostly from the business sphere, see Ari Sharp’s book Risky Business.) The poor and less educated make good villains, too. In the earlier case, also at Jakarta International School (now renamed Jakarta Intercultural School) six janitors were accused of abusing Magic Stone Boy, then five years old. The five janitors that did not die during questioning in police custody are now in jail. The police say the sixth man committed suicide; they did not explain how or why he bruised his own face before killing himself during a break in questioning.

I think that children’s voices should be heard in court. I think that allegations of abuse should be taken seriously. But when medical reports, virology and the early testimony of the children themselves all point to no abuse, we should follow the evidence and common sense. Hard, in this case, since the trial was held in secret, the accused were subjected to gag orders, and the judge set arbitrary time limits on questioning of defence witnesses (though prosecution witnesses were given all the time they needed). It’s hardly surprising that commentators on news of the verdict are happy to believe widespread rumours that the accusations, the evidence-free convictions and and the huge compensation claims are all part of an orchestrated campaign to shut down the school and grab the valuable campus land.

I’m depressed that the judge couldn’t even be arsed to introduce any logic into her ruling. She listed six factors that pushed her to hand down 10 year sentences. I quote from Tempo:

First, the defendant never admit the harassment act that he committed. Second, the defendant never stated that he regretted his act. Third, the defendant never apologized to the victims’ family for what he had committed. Fourth, the defendant is considered to be uncooperative during the trial by giving convoluted statement in the court. Fifth, the defendant formed a public opinion by giving explanation about the case to the press, before and after the trial, whereas the trial is actually a closed hearing… And finally, the sixth, Bantleman was seen as a worst example of a professional teacher by burdening his students with psychological burden instead of protecting them.

In other words, the (foreign) defendant MUST be guilty because he maintains his innocence.

On recent evidence, women, foreigners and the 110 million Indonesians who live on two dollars a day can’t be blamed for thinking that not everyone is equal in the eyes of the law in Indonesia.