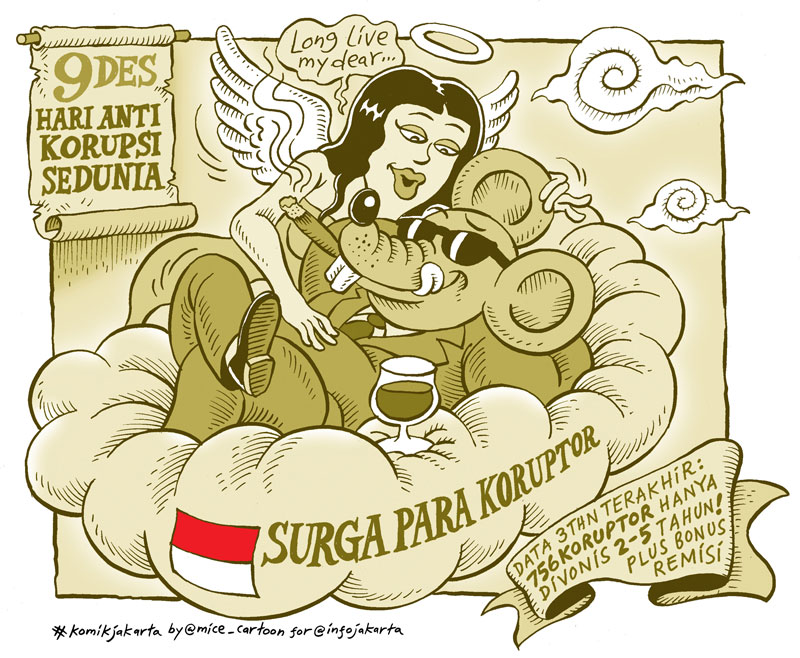

Heaven for Corruptors! The banner gives stats for the length of prison terms for those convicted of corruption. Thanks to komikjakarta.

Today was International Anti-Corruption Day. Staff of Surabaya’s prosecutor’s office gave out stickers that read: “Don’t feed your family on dirty money” and the boss of Indonesia’s national airline Garuda promised to show anti-corruption films on all flights. Meanwhile, the world was presented with a lot of fuzzy claims about what corruption does, though very little clarity about what it is.

Here’s an example from the International Business Times, UK Edition:

Corruption affects all countries, undermining democratic institutions, stunting economic development and contributing to governmental instability. It is the single greatest obstacle to economic and social developmental in the world…

Moreover, corruption leads to weak governance, which fuels organised criminal networks and promotes human trafficking, arms and migrant smuggling and other practices detrimental to human rights.

The article doesn’t define corruption or gives any sources for its claims, but perhaps no-one expects better of the International Business Times, UK Edition.

UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon gives us a similarly sweeping statement, again without much in the way of facts or any definitions:

Corruption is a global phenomenon that strikes hardest at the poor, hinders inclusive economic growth and robs essential services of badly needed funds. From cradle to grave, millions are touched by corruption’s shadow.

Again, perhaps our expectations are not high. I confess, though, that I hoped for better from the World Bank. The Bank is often slow to catch on to what’s going on in the real world — their 2015 World Development Report, published last week, has only just reached the staggeringly obvious conclusion that humans are not robots running software that responds only to rational economic choice models. (You can find an 18-minute version of the same idea in a TED talk I gave five years ago, which itself built on something that all humans other than economists have known since the dawn of time.) But once bank staff do latch on to an idea, they often think quite sensibly about it.

Not, however, when the idea is that corruption is not, necessarily, all bad. I was excited to see that The World Development Report’s first two-page “Spotlight” was called “When corruption is the norm” (pdf). I thought it might give a more nuanced view of the difference between what I call “extractive corruption”, aka graft, and what I call “distributive corruption” (broadly speaking, patronage). As I tried to explain very briefly in a talk at TEDx Ubud earlier this year, it’s an important distinction in massively diverse democracies such as Indonesia. Most Indonesians I have talked to are pretty clear about the difference; they hate graft and throw people who steal for their own comfort and pleasure out of office. But they tolerate and even expect patronage; it’s the basis of most social structures in Indonesia as it is in very many countries. There’s little stomach for the hyper-individualistic social and economic organisation that would criminalise you for helping to get a good job for your cousin once you’ve done well yourself, especially when your cousin’s parents helped pay your college fees. Though the World Bank talks of socially embedded corruption, it still sees patronage as something wicked, something that can and should be eradicated with the help of Twitter campaigns. I disagree.

None of this is to say that old-fashioned graft does not flourish in Indonesia. It does, especially in the judiciary and the police force — I learned a great deal about the latter from the wonderful Jacqui Baker, who spent long, patient months just sitting in a cop shop in Maluku, figuring out who was giving how much to whom for what.* Many types of graft and other abuses of power really are vastly damaging to society. But lumping them together with common patronage is the equivalent of treating advanced cancer in the same way that we treat the common cold, simply because both are “illnesses”. We need better diagnosis of different types of “corruption”, and of the different social, economic and political roles each one plays. That would allow us to attack the cancerous forms more effectively, while finding ways to institutionalise, legalise or otherwise tame the forms that act more like primers to the social immune system.

*Jacqui described what the cops get up to in this discussion with me and others at the Ubud Writers and Readers Festival. I also urge you to listen to her radio documentary about extrajudicial killings by the Indonesian police, Eat, Pray, Mourn. And as I’m on the subject of Jacqui’s work, I might just add a link to her delightfully written review of some recent books on Indonesia.

Interesting thought. How do you think patronage (i.e. selecting public employees by their connections) would be better than selecting public employees by their professional qualities?

@Rolf:

I don’t think selecting on connections is better. But the truth is that in much of Indonesia, especially the newer kabupaten of Eastern Indonesia, selecting by professional qualifications is not really an option, because so very, very few people from that kabupaten (the “putra putri daerah”, or sons and daughters of the region) actually have any relevant qualifications, and the political imperative to appoint putra putri daerah is exceedingly strong. In places such as Solo, or Jakarta (to take two not exactly randomly-chosen examples) a meritocracy is a real option. In places such as Paniai Jaya, where there at pemekaran only four local people were medically qualified, all as midwives, it is much harder to staff the health department on a meritocratic basis. Patronage does not make for an efficient civil service, but in that case it does at least reduce the resentment and friction that occurs when all the best posts go to outsiders.